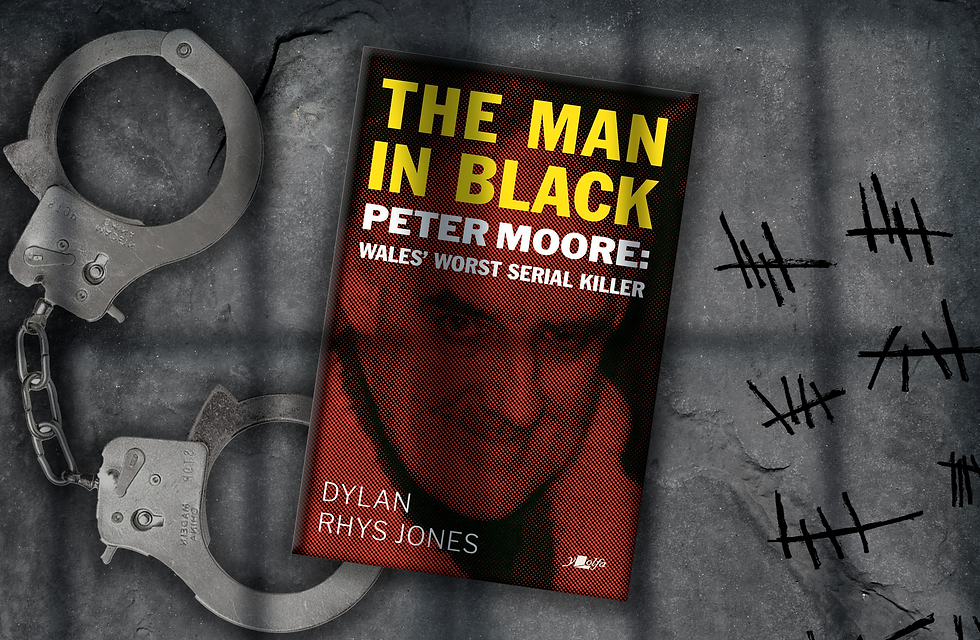

Review 'The Man in Black: Peter Moore – Wales Worst Serial Killer' by Dylan Rhys Jones

- Nov 6, 2020

- 3 min read

In a grey past, I took it upon myself to study law. Fresh out of school and with little sense of direction, I had only a vague notion of what such studies would entail. After two years of battling my way through the courses, with criminal law being my stumbling block, I realised I lacked the passion I knew was vital for becoming a successful lawyer.

In The Man in Black: Peter Moore – Wales’ Worst Serial Killer, Dylan Rhys Jones in many ways has confirmed and enforced the image of lawyer life that deterred me from wanting such a life for myself. The extra hours, digging through piles of files and case law, the tedious waiting for interviews with clients—it’s all part of the job and Jones’ account is not too glamourous. If you’re searching for a story of a big city lawyer flashing dollars living life in the fast lane this is not your book. However, if you’re looking for an honest, unique view into the inner life of a criminal lawyer, you should give The Man in Black a try.

TV shows on law and justice might have caused you to believe that only those with the coldest hearts are capable of defending people who allegedly raped, assaulted or murdered someone. As Jones is well-aware of such views, he counters them early on. He also shows that behind that seemingly impenetrable wall, the hardened face that beams with authority as it vehemently spits out the seeds meant to sow doubt, rests a fragile figure haunted by faces, stories and memories of the most heinous crimes and those who committed them.

Jones comes across as a lawyer with great passion, integrity and unpretentiousness, but also as a human battling with fears and self-doubt. While the former makes him likeable, the latter makes him interesting and relatable. Gradually, his enthusiasm and devotion turn against him, and rather than him consuming the case, the case starts to consume him:

One of my weaknesses as a lawyer was that when I became involved in a case I found interesting and intellectually stimulating, it would then take over my working hours and regularly also all of my free time…I suppose that this was my strength as a lawyer, but also eventually my downfall.

Jones leaves no doubt about the impact such cases have one all people involved, including the defence lawyer:

The truth is that those cases stay with you, become part of your DNA, penetrate into your very being as a lawyer and as a person and challenge you with questions and dilemmas which you may be unprepared to face.

People have always had a deep fascination for horror and death, even if we denounce any form of violence. We willingly devour those terrifying tales of serial killers, the ‘macabre legends told to others so as to chill the blood and unsettle the mind of the listeners’. The evidence against Peter Moore contained countless of documents as well as photographic material, including photos of the victims, which Jones had to study for the purpose of the case. The effects of being continuously exposed to such horror shouldn’t be underestimated. It’s the reality people like Jones, but also police officers and court clerks, have to deal with.

Reading about real-life violence from the lawyer’s perspective, seeing it as Jones did, also painfully lays bare a process in which the general public and media become the perpetrators of another type of violence. In high-profile murder trials victims are often made into a spectacle: stripped of their dignity, they become stories and still images, silenced figures whose eyes scream fear and pain, used in court to make a point. It’s trespassing, horrendous, upsetting. Jones reminds us that

Behind every murder, somewhere on the ground, on a floor, a wall or ingrained into someone’s memory, is a silhouette of a person, lying there dead or dying.

Traumatic memory is at the heart of the story. Through The Man in Black, Jones analyses the effects Peter Moore and his case had on Jones’ own mental well-being. As a criminal defence lawyer, Jones had to deal with the most horrific cases, which for him (and likely many others) meant not dealing with it at all and telling himself ‘it will pass’. It doesn’t pass, though, and it might never will. Let’s hope, then, that for Jones writing The Man in Black was at least somewhat cathartic.

Comments